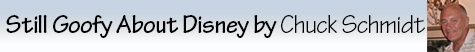

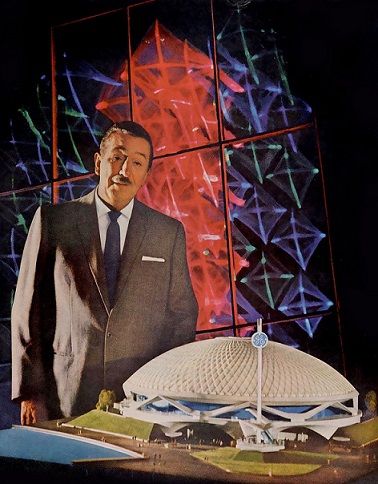

To many long-time Disney followers, the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair was a watershed moment for the Walt Disney Company.

Disney’s participation in the Fair saw the introduction of a radically new form of theme park entertainment, as well as the debut of innovative ride systems that had the ability to handle large audiences in an efficient manner.

And unknown to the millions of visitors during the Fair’s two-year run, Disney’s participation at the Fair was a proving ground … a dry run for Walt’s planned move east to central Florida. At the time, Walt had very real concerns that his brand of theme park entertainment, a big hit on the West Coast, might not be accepted by East Coast audiences. The success of all four Disney shows quelled those doubts and ultimately paved the way for Walt Disney World.

The marriage of Disney and the World’s Fair began several years before the Fair opened, when the entertainment company was commissioned to create and build three attractions: Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln for the Illinois state pavilion; Carousel of Progress for General Electric’s Progressland, and Ford Motor Company’s Magic Skyway. Then, just 11 months before the Fair’s April 1964 opening, Pepsi-Cola convinced Walt to commit to a fourth show, a salute to children around the world that was known as it’s a small world.

“In 1959, Disneyland added Matterhorn Mountain, the submarine voyage and the monorail,” former head of Walt Disney Imagineering Marty Sklar said. “Disneyland was now set for a few years. Walt was able to turn all of his attention to the World’s Fair.”

Committing to the four shows put Disney’s creative staff to the test, pushing them to accomplish more than what was thought possible, all under the caldron of intense deadline pressure. In addition, everything was designed and built at Disney facilities in California, meaning that once the attractions were completed, they needed to be packed up, shipped East and set up at their respective pavilions on the Fair grounds in the New York City borough of Queens. As a result, Disney’s creative team would spend months at a time assembling the attractions in the four Fair pavilions.

While Disney’s four World’s Fair shows were unique and featured vastly different story lines, there was a common thread running through each one … specifically, the first-ever widespread use of Audio-Animatronics figures.

Disney designer Bob Gurr, a self-described “car guy,” and Roger Broggie were tasked with bringing Audio-Animatronics from the drawing board to believable working figures by Walt Disney himself. “Bobby,” Walt would often say to Gurr, “I need you to …” which was followed by a request to pretty much make the impossible not only possible, but a reality.

While working on the ride system for the Ford Magic Skyway, which was a monumental task in its own right, Gurr got his first taste of the new-fangled robots to be featured in Disney’s Fair attractions.

“I was asked to look at the GE animated figures [to be used in General Electric’s Carousel of Progress show] and so that was kind of a shock because I had only done vehicles,” Gurr said. “I had never done any animated humans or animals. I was tasked with gathering up three or four guys and figuring it out.”

As they sank their teeth into the project, Gurr asked a logical question: “How could we do animated figures in a wholesale method?” since the Carousel of Progress would contain 32 figures, both human and canine.

“We tried several different types of animation,” Gurr said. “A couple of the techniques didn’t work, but we came very quickly to learn how we could do it, so I started a whole system of parts numbering, how we would do the engineering, drawing and working with the shops.”

Then, in October of 1963, just seven months before the Fair was to open, Walt dropped another bombshell on Gurr.

“Oh, by the way, Bobby,” the boss said, “I want you to do the Lincoln figure.”

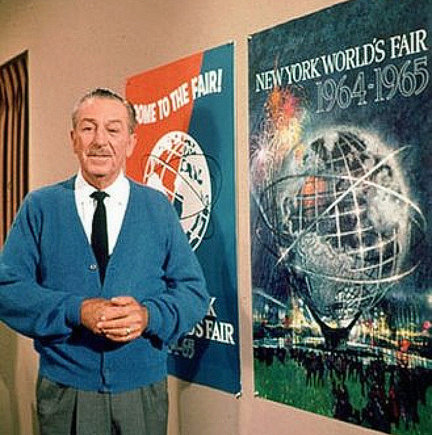

At the time, Gurr was working full-bore on the Ford Magic Skyway ride system, the forerunner of Disney’s PeopleMover, where actual Ford cars would be pushed along a continuous track by motors with wheels embedded in the ground, and was just getting his feet wet on all the Carousel of Progress figures when Lincoln was added to his already full plate.

“Actually, the Lincoln figure was kind of easy,” Gurr says now, more than five decades later. “I had just enough experience with what we had to do with the GE figures. But Lincoln was gonna have to do a lot more animation and do really quite a trick thing.” That “trick thing” was having Lincoln stand up from a chair at the beginning of the show.

“But we got it all done in 90 days … concept, making the sketches of all the parts, passing out the parts to all the drafters, then taking out the parts drawings every day over from Glendale to Burbank at the studio where we were building it.

“It turned out, in hindsight, to be a radical machine, the first time the world was ever going to see a really believable animated figure and then a president of the United States, to boot. Not only that, but he was a tall, skinny guy who didn’t have any body to put parts inside!

“If we’d done Grover Cleveland, I would have had a much easier time … I would have had a lot more room in there!” Gurr joked.

Several problems did surface with the Lincoln figure, most dealing with the amount of electrical current flowing into the Illinois pavilion. No one ever found out exactly why Lincoln would occasionally “spasm” during testing, although the lights at nearby Shea Stadium were the chief suspect.

According to Gurr, “it was a marvel the machine worked as well as it did from the get-go. It combined the sculpting, the skin, the detailed facial animation [done by Disney Legend Blaine Gibson], animated hands, plus the body, plus getting him up and out of the chair and all the electronics to do with that … it was a big effort by so many people working on that machine.

“But within a year, we found with the basic concept of the Lincoln figure, we could actually engineer what we would call production parts. In other words, instead of making a part one at a time, we could make a whole group of parts by investing in the tooling to make parts.”

The development of what Gurr called “standard AA figure parts” enabled Disney to manufacture a wide range of human and animal figures.

“And all of that started with the basic configuration of Abraham Lincoln,” Gurr said.

To play it safe, there actually were two Lincoln figures, with chairs, in the Illinois pavilion. One was positioned on stage, while the other was located below the stage. If there was a problem with the Honest Abe on stage, his stand-in could be brought up in an elevator to take his place. “As it turned out, Lincoln No. 1 ran almost flawlessly through the 1964 and 1965 seasons,” Gurr said.

Gurr also made significant contributions to it’s a small world, devising spinning turntables for several of the animated dolls and working with Arrow Development on the trough and water jet system which gently propelled the boats through the attraction. The boat ride concept worked so well that the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction, which was originally planned to be a walk-through, was changed to its now familiar water-based adventure.

Gurr’s system of developing standardized parts aided in the production of the dinosaurs and cavemen and women featured in Ford’s Magic Skyway, a journey through time from the dawn of man on to the distant future. Some of those original dinos can be seen today in diorama scenes during the train ride at Disneyland.

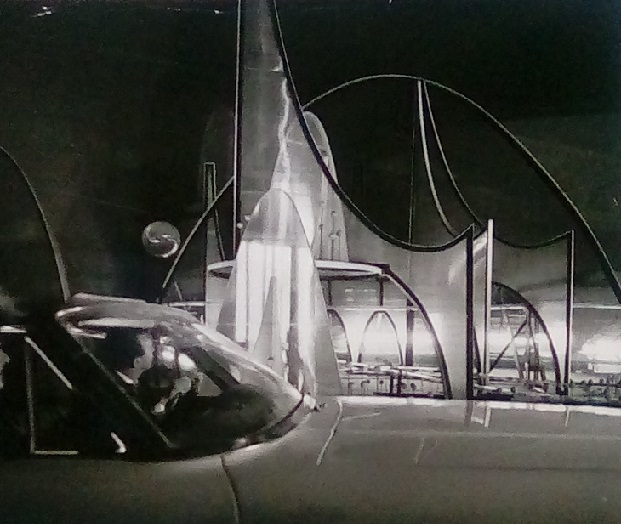

General Electric’s Progressland pavilion, which was in the shape of a giant dome, was perhaps the most diverse of the four Disney-created World’s Fair shows. In addition to the Carousel show, which featured seating areas that rotated around fixed stages, there was a giant area devoted to General Electric product displays, including a look at what a house might look like with all electric appliances. There also was The Toucan and Parrot Electric Utility Show, which proved to be the bane of Marty Sklar’s World’s Fair experience, even though he wrote the script for the show. “Oh, god, I hated it!” he proclaimed years later.

And there was the Skydome Spectacular, which utilized a new projection technique inside the massive dome to showcase natural sources of energy, such as electrical storms, fire, the blazing sun and the show’s climax: The first-ever public demonstration of controlled thermo-nuclear fusion. “Don’t worry,” a hostess calmly announced to the audience, “this demonstration is completely safe.”

During the winter of 1964-1965, between the Fair’s two seasons, Disney addressed a problem that had popped up outside the Progressland pavilion during the opening season. It seems the planners didn’t figure on so many people visiting the attraction, and long lines often backed up outside the entrance and snaked haphazardly in and around an open lot next door … this, despite the fact that about 240 guests entered the attraction every four minutes.

A covered waiting area was erected on that lot between seasons, which kept guests out of the sun during the summer months. And the now-familiar switch-back line system also was installed to keep things far more orderly.

In addition, the GE Progressland pavilion became the first Disney attraction to use a wait time sign, which gave guests an idea of how long their wait would be; similar signs are now employed at the entrances of just about every Disney attraction worldwide.

After guests experienced the Carousel of Progress, they could take a look at Medallion City, Walt Disney’s vision for the future of America’s cities.

“You went into the General Electric exhibit and there were a whole bunch of things there regarding community development,” Sklar said.

There was one final element inside the GE pavilion that impacted Disney’s plans: A VIP Lounge, where GE execs would entertain their guests. Walt Disney was so impressed with this concept, that he decided to create a VIP lounge of his own at Disneyland … which was the impetus for the exclusive Club 33 in New Orleans Square.

When Carousel of Progress was moved to Disneyland after the Fair, a model, called Progress City, was put on display. “The audiences moved up a moving ramp to the second floor in Tomorrowland at Disneyland,” Sklar said, “and there was Act 5, the so-called Progress City model. It was developed from the Herb Ryman illustration of Epcot that we used for many of the publications we did about Walt’s Epcot. That model fascinated Disneyland guests for five years.

“It was basically a depiction of the Epcot community that is represented in Walt’s Epcot Film,” Marty added. Part of that model can be seen today along the PeopleMover route in Tomorrowland at the Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World.

As part of the sponsorship agreement Disney had with all four Disney Fair show sponsors, GE’s Carousel of Progress was transported back to California and opened in Disneyland in 1967. The show debuted in Walt Disney World in 1975, where it still plays to appreciative audiences to this day. The Lincoln show took up residence at the Main Street Opera House in Disneyland in 1965, while it’s a small world found its permanent home in Fantasyland in 1966.

“Walt had written into the contracts that Disney owned each show,” Sklar said. “Basically, all these new attractions for Disneyland were paid for. Everything was transported back to California in trucks, even the troughs for small world.”

There was another element at the Fair that seemed very Disney-esque, but wasn’t: A monorail system.

The Fair’s monorails were built by American Machine and Foundry Co. [AMF]. Unlike Disney’s monorails, which glide on rubber tires atop elevated beams, AMF’s version rode below the beam, connected to overhead power units.

The Fair’s massive monorail station was built from structural steel and Fiberglass panels and you needed to take an escalator to and from the loading platform, which was 40 feet above ground.

Unlike the still-operating monorails at Disneyland, which debuted in 1959, or at Walt Disney World, which began service along with the park in 1971, the World’s Fair monorail system was demolished with the rest of the Fair’s buildings and infrastructure after the second season concluded in October of 1965.

Trending Now

An iconic EPCOT ride got a bit of a refresh recently!

We found your perfect Hollywood Studios tee.

We're a little surprised that these ride trends haven't changed in Disney World yet!

Here are some Disney household items on sale right now from Amazon!

A Disney Channel icon just visited Disneyland and proved that it really is just a...

We're digging into Disney World's Magic Kingdom expansion plans!

One Disney World park is about to celebrate a big milestone!

One of Disney World's parks is about to celebrate a NEW milestone soon and they're...

Don't miss out on these super low prices on Amazon for a bunch of cool...

The way guests pay for Savi's Workshop and Droid Depot is changing!

What's become of Hollywood Studios' opening day attractions?

We have Halloween on our minds and this is how Halloween Horror Nights at Universal...

These are the rides you MUST ride in 2024 -- no ifs, ands, or buts!

It's Gemini season, and for all our Geminis, here are some Loungefly bags that are...

We found a BUNCH of Disney 'Tangled'-inspired LEGO flowers on Amazon!

These 2000+ piece Disney LEGO sets are NOT for the faint of heart...

Want to book a Disney vacation but don't know where to start? We've got an...

Summer events are coming soon to a Disney Park!

Over the years, Walt Disney World has planned numerous Resorts around the Seven Seas Lagoon...

Catch up on the newest Disney menu updates all in one place!