In this blog I’ll finish the story of how Walt’s love for steam trains played an important part in the creation of Disneyland.

As Walt’s dreams grew, so did the size of his Disneyland railroad. Scaled down replicas simply wouldn’t do in his new park. He searched several locations for existing locomotives, but ultimately decided to build his own, using his existing plans from the Lilly Belle. He ordered a large machine shop to be built at the studio behind the Ink & Paint department and construction was completed within 90 days. A staff was assembled and designs started to take shape. With the exception of the wheels and boilers, which were purchased from outside companies, the rest of the locomotive would be built at the studio and completed on-site at Disneyland.

After much tinkering, a 5/8th scale of actual size was ultimately decided on for the rolling stock and engines. To accommodate an engineer and fireman, the cab of the engines would be designed at 3/4th scale.

Reducing standard gauge track by 5/8th brings it to roughly 36 inches. This is the same width as American narrow gauge track. When running a full scale narrow gauge train on narrow gauge track, the engine and cars look oversized. But when reduced to 5/8th scale, they look appropriate to the tracks they’re riding on.

Contrary to popular belief, Main Street at Disneyland was NOT built to 5/8th scale to match the trains. Various scales were used throughout the park to promote forced perspective, giving the buildings a feeling that they are taller than they actually are. Besides the trains, the only structures at Disneyland that are built to 5/8th scale are the horseless carriages and the Mark Twain riverboat.

Initial research indicated that three trains would be needed to handle the crowds, but with the $11 million budget already bursting at its seams, Walt decided to only build two trains for the time being. When additional funds became available, a third train would be added. It was also at this time that Walt decided to construct the railroad with his own money and he owned the trains through WED (Walter Elias Disney), the design arm of the company.

Except for minor differences, Engine No. 1 was almost identical to the Lilly Belle. In an effort to add variety to the park, Engine No. 2 was tweaked. Although identical mechanically, the smoke stack, pilot, headlamp, cab roof, and color scheme were changed.

When completed, the engines cost $40,511 each and their tenders $5,010 each. The passenger train’s six cars cost $93,332 and the freight train’s cars cost $55,691 for a grand total of $240,065.

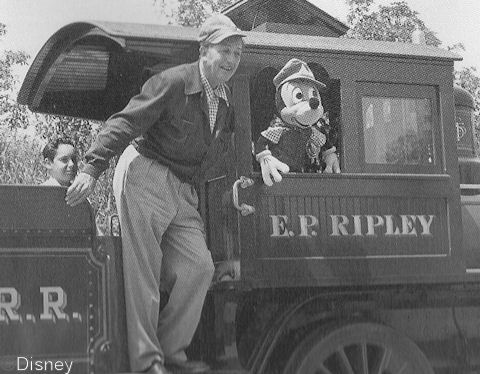

On June 17, 1955, exactly one month before Disneyland opened, Walt took Engine No. 2 out for its first run. Even though the track did not yet circle the entire park, Walt was in his glory running his new engine and stopping for publicity photo ops with his pal Mickey Mouse. With a tremendous amount of work still on the horizon for Disneyland, Walt commented, “At least we’ll have the railroad operating on opening day.”

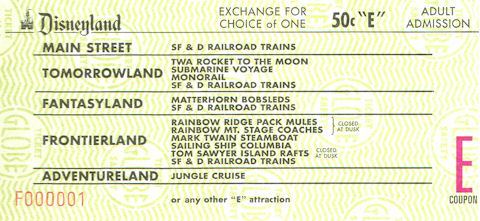

When Disneyland opened on July 17, 1955, general admission was $1 for adults, 50¢ for children, and parking was 25¢. Ticket books had not yet been envisioned and each attraction required a separate ticket to be purchase for cash at various kiosks located around the park. The train cost 50¢ for adults and 35¢ for children to ride. Ticket books were introduced in October of that year and featured A, B, and C coupons – of which the railroad was a “C.” In 1956 the “D” ticket was introduced and in 1959 the “E” ticket came into being where the Santa Fe & Disneyland Railroad remained for many years.

The Santa Fe Railway Company was one of the original lessees (now participants) and paid $50,000 per year to have their name displayed on the trains, posters, trestles, tickets, and other railroad related items. In addition, Walt agreed to name train No. 1 the C. K. Holliday for the Santa Fe founder and train No. 2 Edward P. Ripley for the line’s first president when the company reorganized in 1895.

In the beginning, there were two different types of rolling stock for the Disney trains, the passenger cars and the freight cars. The passenger cars worked well enough, but the freight train consisted of three cattle cars, two gondolas, and a caboose. Those relegated to the cattle cars complained that they felt like, well, cattle and weren’t happy with their place on the train. And besides that, it was difficult to see anything as the opening between the car’s slats was only four inches wide. It didn’t take long to realize that something needed to be done and the cattle cars were eventually reworked to afford better viewing.

With attendance booming, it became evident that a third engine would be needed sooner, rather than later. But this time, instead of building an engine from the ground up, the Disney team decided to buy an old engine and refurbish it. After some scouting, they found an 1894 Baldwin locomotive that had once hauled sugar cane to and from New Orleans. It was in dreadful shape, but had potential. Negotiations began and a price of $1,200 was eventually agreed upon.

After much work, the new engine began service on March 28, 1958. The final cost was $37,061 for its purchase and restoration, far below the $100K that it would have cost to build an engine from scratch. The No. 3 engine was named Fred Gurley after the chairman of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Company.

The loading and unloading of the passenger train was slow and time consuming as there were only doors at the front and back of each coach. For the Fred Gurley, a Narragansett-style open air coach was designed by Bob Gurr. The train would feature forward facing seats and each seat could be accessed directly from the station platform, facilitating a much faster loading process. In addition, the new design allowed for 325 guests compared to 268 held by the passenger train.

Have you ever wondered why there are two sets of tracks in front of the Disneyland Main Street Station?

When Disneyland opened, there were only two stations, Main Street and Frontierland. One train would make a complete circle around the park without stopping, beginning at the Main Street Station. The other train would circle the park starting from the Frontierland station. Because of this, there needed to be a second set of tracks at each station so one train could pass the other while circling the park. By 1958 this practice was ended when the Fred Gurley joined the two original engines and the Fantasyland and Tomorrowland stations opened.

The section of track between Tomorrowland and Main Street passed backstage areas so a wooden tunnel was constructed to conceal this from the guests. To improve this boring section of track, Walt ordered a new show piece for his train, the Grand Canyon. A diorama painted on a seamless piece of canvas measuring 306 feet long and 34 feet wide depicted this natural wonder. Now instead of a boring tunnel, guests are treated to a depiction of an entire day at the Grand Canyon from daybreak to sunset, complete with thunderstorm. Grofe’s Grand Canyon Suite can be heard from onboard speakers. This new addition cost $367,814 and opened March 21, 1958.

It was determined that a fourth engine was needed so that the other three could occasionally be taken off line for maintenance. Once again, a scouting team found an old locomotive, this time a Baldwin 0-4-0T that was built in 1925 and hauled sand to builders in the Northwest. It was purchased for $2,000 and shipped to the studio for refurbishment. Named the Ernest S. March after the current president of the Santa Fe Company, engine No. 4 went into service on July 25, 1959.

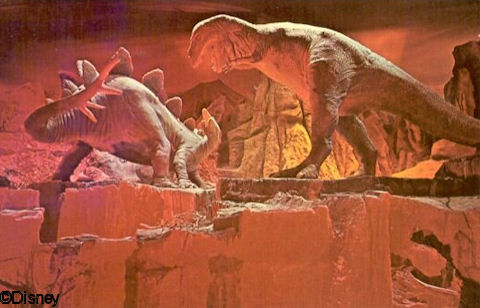

The Ford Motor Company approached Walt in 1963 and asked him to create an attraction for the upcoming 1964 New York World’s Fair. Walt agreed and when completed, the ride allowed guests to travel back in time aboard a Ford convertible and witness cavemen and dinosaurs as never seen before. Audioanimatronics were used on a grand scale and guests were impressed beyond belief. When the fair closed in 1966, Walt packed up the dinosaur section of the attraction, shipped it to Disneyland, and added a second diorama to his railroad. Only this time, it would not be stagnant as the Grand Canyon diorama was. Like the World’s Fair, guests were amazed by the movement of these prehistoric monsters. Disney movie buffs might recognize many of the scenes as they were modeled after the “Rite of Spring” segment of Fantasia.

As WED Enterprises grew more and more entwined with the studio, Walt decided to sell the design portion of the company, now known as Imagineering, back to the studio in January 1965. However, he retained the rights to his name, the steam trains, the monorails, and his apartment over the Fire Station on Main Street. A new company was created to manage these assets and named Retlaw (Walter spelled backwards). The family owned the trains for many years until they finally sold them back to the studio in 1982 for 818,461 shares of Disney stock.

In 1999, the Disney Company purchased its fifth steam locomotive from the Cedar Point Amusement Park and in 2004 it entered service at Disneyland. Engine No. 5, was named Ward Kimball in honor of the man responsible for getting Walt hooked on model railroading.

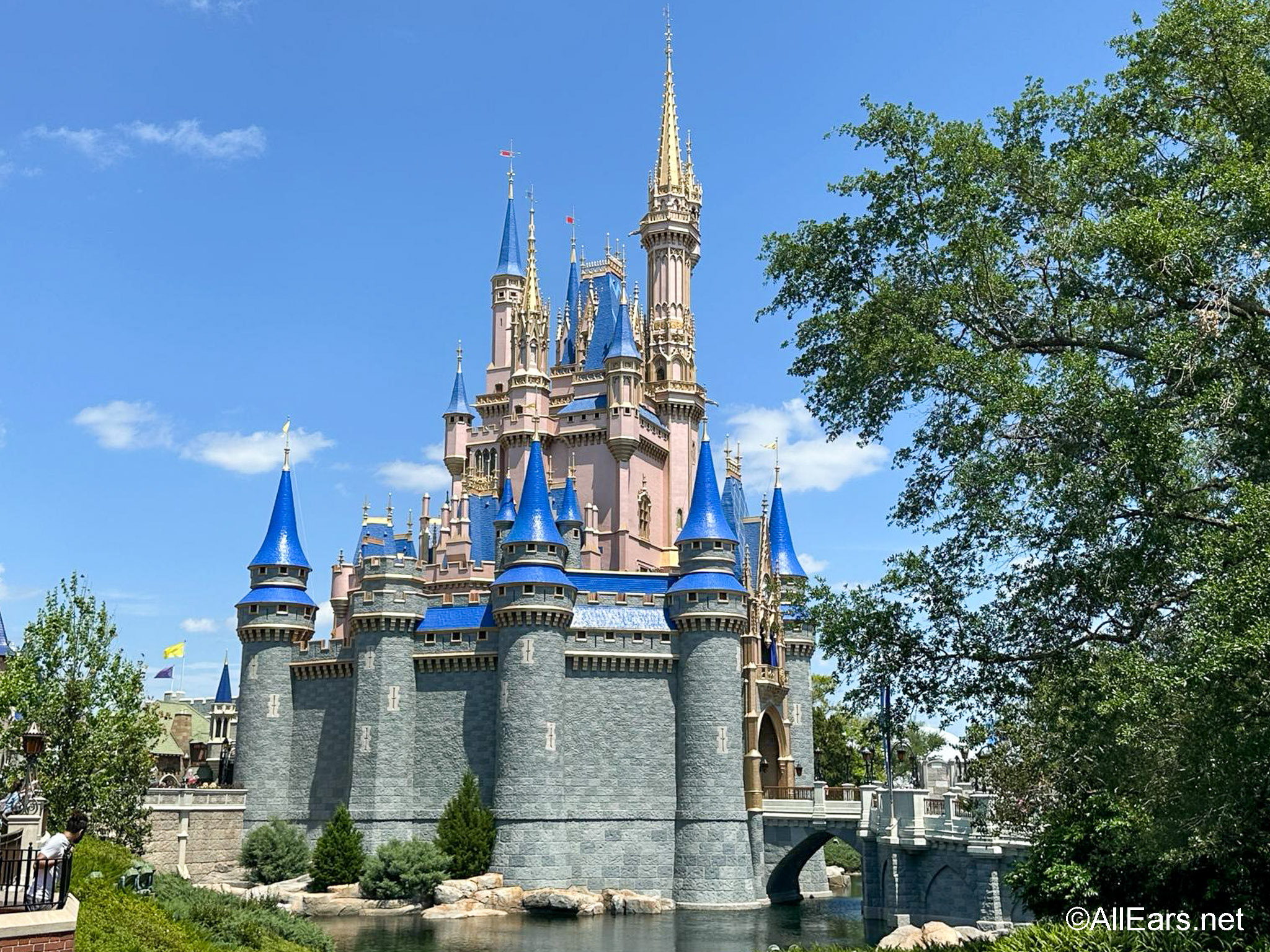

Check back tomorrow when I discuss the steam trains of the Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World.

Hey Jack,

What informative blogs about how trains brought about Disneyland! I don’t know near as much about Disneyland as I do WDW, so all of this was new information to me.

I’ve seen a lot of pictures of Walt Disney, but never have I seen his face light up as when he was on a train. Such a multi-faceted man who loved to share his interests with the world.

Can’t wait for your blog tomorrow!

-Kirstin