Sometime ago, this article appeared in the AllEars® Newsletter (Part 1 and Part 2). Since not all of you receive this weekly publication, I thought I’d rerun it as a blog and add a few pictures. Enjoy.

——————————————————————————————–

What is to follow is a brief history about Walt’s passion for steam trains and how this loved helped build Disneyland and four other theme parks around the world.

Before I start this article, I want to say that the vast majority of the information I present here is from the book “Walt Disney’s Railroad Story” by Michael Broggie. This is an excellent book, not just for railroad buffs, but for anyone interested in the history of Disney theme parks. What I offer below just barely scratches the surface of what this remarkable book has to offer. I would highly recommend purchasing it and it’s sold on Amazon. Click here.

We’ve all seen the television interview of Walt Disney, describing how the idea of Disneyland came to him. He recalls a day when he was sitting on a park bench, watching his daughters ride the merry-go-round, and thinking to himself that there should be someplace created where children and parents can play together.

This is a charming story, told by a charming man, and its telling has delighted viewers for years. But this is also the simplified account of how Disneyland came into being. As lovely as this legend is, there is far more behind the birth of Disneyland than this one defining moment – and steam trains played an essential part in the building of the Happiest Place on Earth.

From his earliest memories, Ward Kimball (an animator at the Disney Studios) had a passion for trains. In 1938, he and his wife Betty purchased a full-sized 1881 narrow-gauge Baldwin steam locomotive from the Nevada Central Railroad and spent a number of years restoring it to its former glory. He ran his prize in his own backyard.

In 1945, Ward was hosting a “steam-up” party for the local Live Steamers club and invited his boss, Walt Disney, to be the guest engineer for the event. Ward recounts that he never saw Walt smile more broadly than the moment when he pulled the throttle and the engine emerged from the roundhouse. By the time the party ended, Walt was hooked and railroading was in his veins.

In 1948, Walt discovered that another of his animators, Ollie Johnson, was also a railroad buff and was building a 1/12 scale live steam locomotive to be run in his backyard. Walt was fascinated with the idea and when the engine was completed, he visited Ollie’s home numerous times to play with this intriguing new toy. As Walt’s interest continued to grow, he searched for others involved in the hobby and after many inquiries eventually made the decision to build his own backyard railroad.

Of course, if he was going to build a locomotive, rolling stock, and tracks to run it on, he would need a suitable backyard. So on June 1, 1949, Walt and his wife Lilly bought five acres of land in Holmby Hills, a stylish subdivision located between Bel Air and Beverly Hills.

Next, Walt turned to master draftsman, Eddie Sargeant, to help him develop a track layout for his new railroad. After several weeks of planning, Eddie came up with a design that squeezed 2,615 feet of track and 11 switches onto the property. Besides encompassing most of the back yard, Walt insisted that the train run completely around the house. At 1/8th scale, that was equivalent to eight miles of track.

Lillian Disney was a good sport, but she had her limits. She had selected a large section of the property for her flower beds and she did not want her husband’s trains to run through the middle of this area. To appease his wife, Walt had a gag legal contract drawn up between himself, Lilly, and his two daughters, Diane and Sharon, giving him legal ownership and control of the railroad. And as an incentive for her to sign, Walt agreed to build a 90 foot tunnel under her proposed garden. With a sigh, Lilly acquiesced, put pen to paper, and the Carolwood Pacific Railroad was born.

Now that the right-of-way was secure, Walt needed to start construction on his locomotive. As modern and European engines did not appeal to him, he decided on a more ornate locomotive, the type that were used to build America. After much research he selected the Central Pacific 4-4-0 No. 173 for his prototype. This engine was in service primarily in Northern California between 1864 and 1909.

Just like with his company, Walt wanted to be involved in every aspect of his new hobby. Roger Broggie was a precision machinist at the studio, and under his watchful eye, Walt studied blueprints and learned how to operate machine tools. Over the months to come, Walt worked side by side with the studio mechanics and built a working locomotive completely from scratch. Nothing on it had been purchased “pre-built.” To honor his ever tolerant wife, Walt named his new engine the Lilly Belle. The total cost for his locomotive, rolling stock, and backyard layout came to $50,000. That’s roughly $450,000 in today’s dollars.

Walt normally insisted that his personal life be kept private. But word of his fantastic train layout spread and the Carolwood Pacific was the cover story for several railroad enthusiast periodicals. He even allowed Look magazine to write a feature article and photograph his backyard layout. These stories only fanned the flames of public interest and letters started to flow into the studio, asking for permission to visit his estate and the Carolwood Pacific Railroad.

With the public’s interest in his train growing, Walt started to think about putting some kind of scale model train on the studio backlot for visitors to ride on the weekends. As his ideas grew, he thought about developing the land next to the studio and turning it into some sort of entertainment park. He remembered Ward Kimball’s full-scale narrow-gauge railroad and the idea of owning his own “real” train took root.

In the winter of 1951, famed illustrator and railroad enthusiast, Harper Goff was in London to purchase two 1/8 scale steam locomotives for his own layout. However, when he arrived at the shop, the clerk informed him that they had just recently been purchased by a famous American named Walt Disney. Dejected, Harper searched for Disney and found that he was staying at a nearby hotel. He arranged a meeting and desperately tried to convince Walt to sell him one of the engines. Walt declined, but invited Harper to dinner. As the evening progressed and the admiration between them grew, Walt shared his ideas for a park to be named “Walt Disney’s America.” Harper was intrigued and by the time dinner was over, he had joined Walt’s exclusive team to help design The Secret Project.

Interestingly, the two engines that Walt had snatched from under Harper Goff’s nose were badly damaged while being shipped home. Despite efforts by the studio mechanics to save them, they never did become operational.

At the same time, storyboard illustrator Ken Anderson was working on another project. He was given the task of developing 24 miniature scenes depicting American folklore. Walt wanted Ken to study the technique of Norman Rockwell as he felt this artist had a flare for storytelling and his illustrations appealed to Walt’s Midwestern upbringing and humor.

A 1/8th scale mock-up of “Granny Kincaid’s cabin” was completed and Walt planned to display this tableau and the others on a specially designed train. This traveling show would stop at railroad stations around the country and school children would be invited to experience a three-dimensional history lesson. Walt was very proud of this idea and was excited to show off his first prototype. Granny’s cabin can be seen in the One Man’s Dream attraction at Disney’s Hollywood Studios.

But Roger Broggie did not share Walt’s enthusiasm. He explained to Walt that the miniature scenes would be expensive to create and maintain. Also, the operation of a full scale train would be expensive and the show’s capacity would be limited due to the narrow passageways in train cars. Bottom line, it would be very difficult to make money with this project.

Never one to give up on a good idea, Walt started to rethink the concept. Instead of displaying the miniatures on a train, why not create some sort of “Opera House” and share his tableaux with the guests that visited his studio.

In the spring of 1953 an incident happened that shook Walt greatly. It was a Sunday afternoon and as usual, Walt’s backyard was full of invited friends and business associates. A guest engineer was at the throttle of the Lilly Belle and took a curve too fast. The train tipped over and broke the whistle off of the engine, releasing a jet of high pressure, invisible steam. One of the passengers, a five year old girl, was unhurt by the derailment, but she ran through the jet of steam and received painful, although not serious, burns on her legs.

Walt was greatly upset by the incident. The idea that this little girl, or anyone else, could be hurt by something he had created was too much for him to bear. The next morning he had Roger Broggie drive out to his house, pick up the Lilly Belle, and store it at the studio. The rolling stock was put into the 90 foot tunnel for safekeeping and he halted work on a second engine that was under construction. Bob Gurr recalls that Walt would occasionally visit his beloved Lilly Belle and always touch it affectionately.

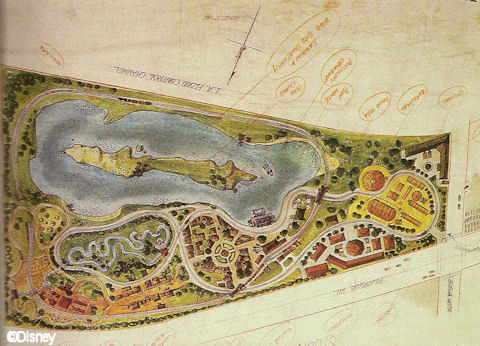

Even after this jolting incident, Walt was still interested in building a small park next to his studio and opening it to paid guests on the weekends. His plans called for a safer Carolwood Pacific Railroad to be part of his project. Harper Goff and Eddie Sargeant created plans for a 16 acre park that would include a 1/8th scale railroad, a circus tent, carousel, old west town with riverboat, Victorian village and picnic area.

But the land Disney wanted to develop was next to the Los Angeles River (a flood control channel) and the soon to be built Ventura Freeway. Fighting “City Hall” to obtain the needed permits to utilize this land proved daunting and eventually, Disney gave up. And by this time, his imagination had outgrown the 16 acres next to his studio.

The search was now on for a large piece of flat land, big enough to hold Walt’s ever increasing ideas. Eventually, a spot was found in Anaheim and negotiations began with 17 families who owned contiguous parcels of land. In the end, Disney acquired 160 acres on which to build his new park Disneylandia, later to become Disneyland. Initial projections suggested that Disneyland would cost $11 million to build and first-year attendance would be between 2.5 – 3 million.

Even for a company the size of Disney, $11 million was a lot of money in 1953, so Walt turned to his financially savvy brother Roy for help. Roy immediately went to work and started negotiating with some New York investors. On Thursday, September 24, Roy received word that the investors wanted to meet with him the following week. Knowing that visual representations help sell a product, Roy told his brother that he needed some sort of rendering of Disneyland to present at his meetings. Since most of the ideas for the park were scribbled on scraps of paper and still in the minds of Walt and a select few, Walt called a friend and former employee of his, Herb Ryman.

Herbert “Herb” Dickens Ryman had previously worked with Walt on such projects as Pinocchio, Dumbo, and Fantasia. He was known for his talent in oils, pen & ink sketches, and especially watercolors. He had also been employed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and 20th Century Fox and worked on a number of their movies.

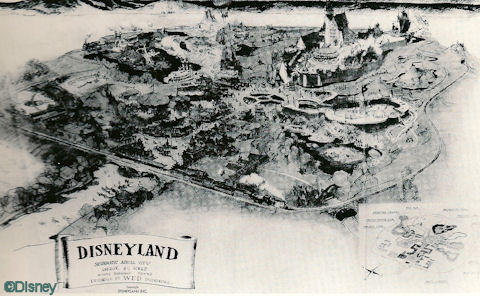

After much cajoling, Herb finally agreed to draw the first interpretation of Disneyland. Herb listened carefully as Marvin Davis, Dick Irvine, and Walt explained their ideas. Eventually, Marvin and Dick removed themselves from the meeting and Herb and Walt spent the entire weekend alone, creating an overview drawing of Disneyland. At the entrance to the park was a Victorian train station with tracks that completely circled the many lands of Disneyland.

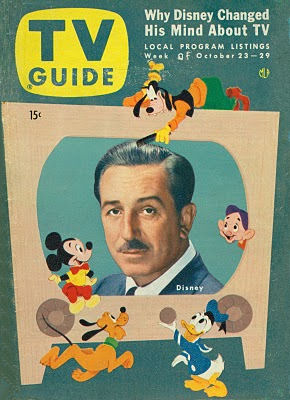

Roy took Herb Ryman’s rendering to New York and met with executives of NBC and CBS. Both companies were interested in Disney films, but had no desire to invest in such a risky venture as a theme park. Then Roy turned his attention to the fledgling ABC network. After much persistence, Roy convinced Leonard Goldenson, head of the network, to invest $500,000 in the park plus loan guarantees for $4.5 million. In return, Disney gave ABC a 35% interest in Disneyland and agreed to produce a weekly one-hour television show.

On October 27, 1954, the “Disneyland” show premiered with Walt as its host. This made him a national celebrity and allowed him to “advertise” his new park as each episode revolved around one of the “lands” to be built at Disneyland. Both new footage and old movies and cartoons were used in production. The show was an instant success and ABC achieved top ratings. In 1960, Disney was able to buy back ABC’s 35% ownership of Disneyland and in 1996, Disney purchased ABC outright.

To help promote Disneyland, the Lilly Belle was taken out of moth balls and returned to Walt’s home. A number of Live Steamer club members and Kirk Douglas’ family were invited to spend an afternoon playing with the Carolwood Pacific Railroad. The afternoon was casually filmed and some of the footage was eventually shown on one of the “Disneyland” television shows.

With financing secured, Walt announced that his new park would open in July, 1955. Ground breaking occurred in August 1954, which only allowed an eleven month window for construction. Since this article is primarily about Walt and his trains, I’m going to concentrate on that aspect of the building of Disneyland.

Check back tomorrow for Part Two where I’ll complete the Disneyland story. In Part Three I’ll discuss the Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World. And I’ll finish everything up in Part Four when I talk about Tokyo, Paris, and Hong Kong.

Hi Jack,

Thanks for another interesting look into what made Walt Disney tick. It’s really fascinating that even when his ideas were shot down he would just bounce back with yet another idea.

Looking forward to the remainder of these articles.

As an aside note, when can we expect to see your reviews on Wilderness Lodge and Pop Century like you did for Riverside?

Wendy Crober

ALLEARS: The Pop Century and Wilderness Lodge Reviews are in the pipeline!

Jack–Thanks for a great blog on something near and dear to my heart…Walt, Lilly, and their steam trains. Michael Broggie does an excellent job of keeping this history of the trains alive, along with the Carolwood Pacific Society. As always, love the history and the little stories that I had forgotten about until you reminded me. Thanks again for sharing with us your knowledge about this great, great man.

Helen

Hi Jack,

What an interesting blog! I love History and especially when it’s about Walt and his trains.

Here in central PA we have a famous landmark called the Horseshoe Curve and if you are interested in reading more train history you can check this out here:

http://www.trainweb.org/horseshoecurve-nrhs/Altoona_area.htm

Jack,

Thank you for posting this today, and I look forward to Part 2. I also wanted to tell you thank you for your blog several months ago on One Man’s Dream. Because of what you wrote, I talked my family into visiting it, and we all thoroughly enjoyed it. I learn so much from your blogs! Thank you!

Thanks for sharing! That’s really interesting! I can’t wait for the rest!

Hy Jack, again from Buenos Aires, I cannot wait to read tomorrow´s part. I love to learn about wdw and disney history, and you are an open book. Thank you for share and write this wonderful blogs!