Disney Legend Marty Sklar will always be remembered for his contributions to the company as the creative leader of Walt Disney Imagineering. It was his skill as a writer, however, that first got him in the door at Disney and which quickly endeared him to Walt Disney himself.

After impressing his boss with the creation of The Disneyland News just weeks before the park opened in 1955, Walt tapped Marty to write his personal speeches and messages. Marty also wrote presentations to would-be sponsors, annual reports, publicity and marketing materials for the Disneyland public relations department at a time when “Disneyland still wasn’t a slam dunk,” as Marty put it.

Even after Walt pulled Marty away from Disneyland and reassigned him to WED Enterprises [the forerunner of Walt Disney Imagineering] in the all-hands-on-deck effort for the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair, Marty continued to write.

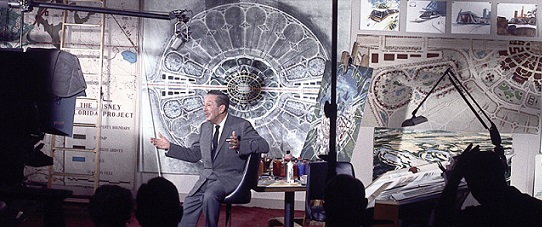

He wrote the scripts for two shows at the Fair — the narrative for the Ford Magic Skyway attraction and the storyline for The Parrot and Toucan show presented inside the General Electric Progressland Pavilion, which featured the iconic Carousel of Progress attraction and, of all things, the first demonstration of controlled thermo-nuclear fusion.

The Parrot and Toucan show was easily Marty’s least-favorite work. “Oh god, I hated it,” he said with obvious anger in his voice decades after the fact. “The show was about a parrot and a toucan talking about atomic energy,” Marty said. “I remember writing nine different scripts and I finally said to the guy at GE I was working with: ‘Who am I writing this for?’ and he said it was for his bosses, not for anyone else. And I said, ‘Not for the public?’ and he said, “My four bosses like it.'”

The World’s Fair was closed over the winter months between its 1964 and 1965 seasons, and during this time, Ford Motor Company chairman Henry Ford II decided he wanted to tweak the Magic Skyway attraction by having Walt Disney recite the narration. Marty Sklar had written the original script, which was read by veteran television announcer Dick Wesson during the first year of the Fair’s run in 1964.

Guests who rode the Magic Skyway were seated in brand new Ford Motor Company cars, which took them on a journey through time, from the dawn of man, into the prehistoric era of dinosaurs, right on through to the far-off future. During the trip, a narrator’s voice could be heard through each of the car’s radio speakers. Paired with background music composed by George Bruns, the show was dramatic, informative and entertaining … as well as extremely popular.

In the weeks leading up to the Fair’s opening, Marty could be found inside the Ford pavilion, meticulously marking the spots where speakers should be placed, thus ensuring the music and the sounds of the grunting dinosaurs and cavemen were in sync with the narration and the movement of the vehicles. Just days before the attraction opened, Marty was back inside, remarking those same spots because painters had unwittingly covered over his original marks!

When Walt found out about Ford’s desire to have him re-record the narration, he was hesitant, but finally acquiesced.

Marty remembers the actual recording session and how difficult it was for his boss. “We recorded Walt early in the morning in early 1965 at the Disney Studios,” Marty said. “He had a terrible cough and kept blowing the lines.”

At the beginning of the session, every time Walt tripped up, he was apologetic. “Pardon me,” he said at one point after fumbling a line. But as the day wore on, Walt got frustrated. “He’d say, ‘Marty, are you sure these dinosaurs are spelled correctly?’ Yes, Walt, I got the spellings right out of the dictionary”, I’d tell him.”

The more frustrated he got, the testier he became.

“When he blew the lines, the language was not what you’d expect. He said, ‘Marty, you’re going to cut out all this shit before you send it back to Ford, right?’ It took a long time, but we finally got a great take.”

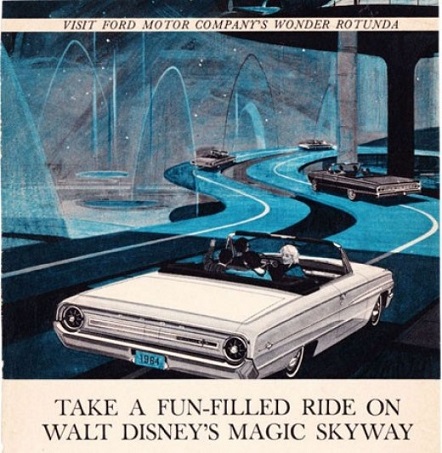

There were several not-so-subtle hints at the World’s Fair that Walt Disney’s fertile imagination was looking beyond the 1960s and deep into the future. In the General Electric pavilion, after guests experienced the Carousel of Progress, they could take a look at Walt Disney’s thoughts on what the future could look like.

“You went into the General Electric exhibit and there were a whole bunch of things in there regarding community development,” Marty said. Years later, when Carousel of Progress was moved to Disneyland, a model, called Progress City, was put on display for guests to view after the attraction.

“The audiences moved up a ramp to the second floor in Tomorrowland at Disneyland,” Marty said, “and there was Act 5, the so-called Progress City model. It was developed from the Herb Ryman illustration of Epcot that we used for many of the publications we did about Walt’s Epcot.

“What Walt had decided was that we should do a model of this concept called Epcot, and we built this big model that was upstairs on the second floor in the Carousel pavilion. That model fascinated Disneyland guests for five years. It was basically a depiction of the Epcot community that is represented in Walt’s Epcot Film.”

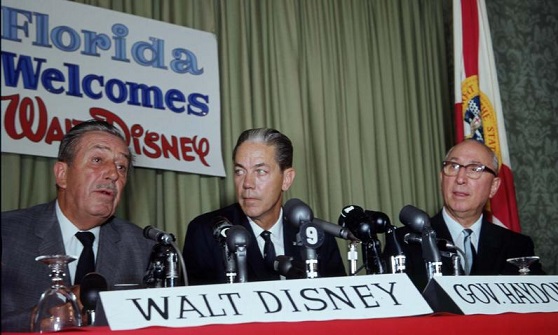

In November of 1965, Walt and his brother Roy sat with Florida Gov. Haydon Burns at a press conference to announce the Walt Disney Company’s intentions to move to central Florida. The conference was short in details, other than the fact that the new entertainment venture would be located in Orange and Osceola counties and that it would not be called Disneyland.

Walt spoke in vague terms, saying the new project would be “fresh and unique” and that there would be two incorporated communities, one named Yesterday and the other Tomorrow. He had been dropping hints about a City of Tomorrow for years, but he admitted that such a city might be outdated before construction could be completed.

In the months following the press conference, the company forged ahead and began firming up plans for what was now known as Epcot … an experimental prototype community of tomorrow.

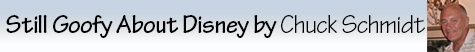

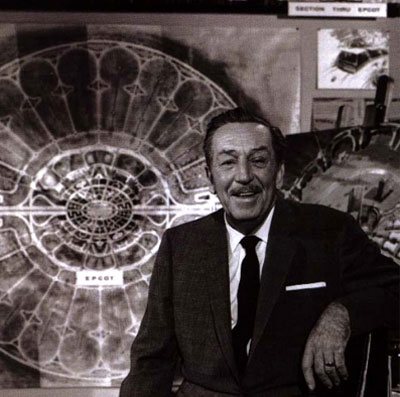

The Epcot Film, which outlined in exact detail the concept for that Utopian city of tomorrow, would become a signature moment of Marty Sklar’s career. As Walt’s go-to wordsmith, Marty was tasked with writing the script for what is arguably the most significant presentation of Walt Disney’s life.

“We wanted a way to show what Walt had in mind, and so I got the assignment [of writing the script], working with two great people – Ham Luske, who was a great animator in the ’30s, and Mac Stewart. [The two had a long history with Disney and, in fact, Hamilton Luske and McLaren Stewart were both listed in the credits for the TV show Disneyland Goes to the World’s Fair]. They got the assignment to be the director and producer of this short film, 24 minutes long, and I got the assignment to write it,” Marty said.

During late summer of 1966, Marty spent considerable time in Walt Disney’s office in Burbank, Calif., feverishly taking notes as Walt fine-tuned his concept for Epcot, in preparation for making the definitive film about Disney’s still-secretive plans for Florida.

“I had several meetings with Walt. He made it so easy for me to write because I could go back to those notes and say, ‘OK, this goes here and this goes here in the script, etc., etc.’

“Of course, we had no idea that he was dying.”

By early in October, Marty finished the script and Walt gave his approval. “I’ve got his handwriting on the original script, which gave Ham Luske and Mac Stewart the go-ahead to make the rest of the film,” Marty said.

Filming took place in late October of 1966. “That was one of the gems of my experience, spending a whole day on the set with Walt Disney while he did so many different pieces of this film. His part took a full day, because there were so many changes that had to be made and shot, in front of all the artwork. We shot close-ups and shot stuff related specifically to the Epcot community.” Walt’s deteriorating health also contributed to the long day: He needed to take breaks between takes to be administered oxygen.

“The first part [of the film] was establishing Disney coming to Florida, talking about Disneyland and what he had accomplished at Disneyland,” Marty said. “And then the big thing was he wanted two endings for the film. He wanted one which would go to the Florida legislation so they could see exactly what he was doing.”

The other ending was for corporate America. “He always emphasized that no one company could do this by themselves, and so he wanted me to write a second ending to the film, which was directed at American industry, so we had two endings that could be used depending on who the audience was.

“The big audience was the state of Florida, so the Florida legislature got the ending that said, ‘It’s really up to you whether we do this project at all,’ that’s exactly what he said.”

Ultimately, the Reedy Creek Improvement District was approved by the state of Florida, giving Disney near autonomous control of development of the property, and the project moved forward. An opening date of Oct. 1, 1971, was set for Phase I, the Magic Kingdom theme park.

The Florida film “was not finished until almost the end of October and it actually was the last thing [Walt] ever did on film before he went into the hospital,” Marty said.

Walt Disney died less than two months later and Epcot would be put on a back burner. His brother, Roy O. Disney, took over the reins of the company and made sure that Disney World — which he insisted on renaming Walt Disney World, thus ensuring that his brother’s name would live on in perpetuity — would open on time.

Marty Sklar would rise up the ranks of WED Enterprises and Imagineering and would become a key player when new Disney CEO Card Walker decided to dust off the Epcot project and bring it life in the 1980s. Throughout the next few decades, Marty oversaw development of Disney’s parks in Japan and Hong Kong in Asia, as well as two outside of Paris, France, two additional parks in Walt Disney World and one alongside his beloved Disneyland.

When he retired on 2009, he was rightly named a Disney Legend and took up a new challenge after being named an ambassador for Walt Disney Imagineering: Giving talks and presentations to large groups of appreciative audiences around the world in hopes of inspiring would-be Imagineers.

In 2013, he returned to writing with the release of his memoir, Dream It! Do It! That book was followed up by One Little Spark!, which gave his readers a look into what it takes to become an Imagineer. And we eagerly await the release of his last book, which he was working on before his death on July 27, 2017.

Trending Now

Here's why I avoid the most popular park in Disney World, Magic Kingdom!

Disney is gearing up to make your vacation wishes come true with a free 7-night...

A new Tangled ride is coming to Disney's reimagined Paris park.

Grab it while it's on sale!

A Disney Springs area hotel is CHANGING -- here's what we know.

Are we excited for Tiana's Bayou Adventure to open? Absolutely! Are we nervous about its...

We are rounding up six Loungefly bags that are perfect for Taurus signs!

McDonald's has brought back a limited-time sandwich, but has given it a SPICY twist!

Your jaw will DROP when you see the NEW Disney popcorn buckets coming soon!

These things SURPRISED me on my week-long Disney cruise!

We're taking a closer look at Disney World's newest gift shop!

A fantasy theme park is closing permanently.

You might want to skip visiting Disney World this weekend.

We asked our readers about their favorite and least favorite hotels, let's see what they...

Here are all the pool closures you need to be aware of in Disney World...

Here are some Disney World essentials and household items on sale right now from Amazon!

Who is excited for summer? There is a new collection online at Target that Disney...

Here are the t-shirts that every Disney Dad will be wearing to Magic Kingdom from...

Hollywood Studios is full of some pretty intense rides, but these are the ones AllEars...

This coaster is pure nightmare fuel.