The next time you have the opportunity to watch a classic Disney movie, such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs or Bambi or Pinocchio, make sure to read the opening credits.

Some of the most famous animators to have ever put pencil to paper for the Walt Disney Animation Studios will be listed. You’ll see names like Ward Kimball, Frank Thomas, Woolie Reitherman, Ollie Johnston and Marc Davis.

Giants of animation, to be sure. But the fact of the matter is, their success wouldn’t have been complete without the contributions of the scores of women who turned their sketches into camera-ready cels.

The names Ruthie Tompson, Marge Champion or Arlene Ludwig probably don’t ring a bell. The same likely holds true for Hazel Sewell, Mary Weiser or Lillian Bounds.

But for every well-known artist in the Disney fold during the Golden Age of Disney animated films, there were 10 women working behind the scenes, most toiling as inkers and painters. Their job was to transform the artists’ rough pencil sketches into sharp, colorful works of art on celluloid sheets that ultimately would become a full-length animated motion picture.

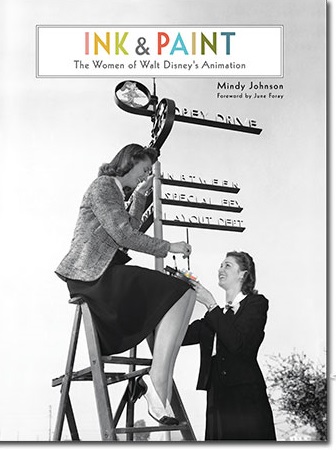

These women, whose anonymity belied their vitally important contributions and their talent, are the subject of a new Disney Editions book, Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation, by Mindy Johnson. More than a deep dive into the history of Disney animation, Ink & Paint is a celebration of the women who not only received little credit for their artwork, but often had to endure difficult working conditions to make each film the success it became.

“I had always been fascinated with the [Ink & Paint] department,” Ms. Johnson said in a recent interview. “I would find myself walking through the hallways and peering in on all those extraordinary colors. When I pitched the idea to my editor, we both thought it would be a charming little volume on tea cakes and tea time, paint smocks and the tunnel of love.

“Everybody underestimated what was going on there.”

It took five years to put together Ink & Paint, which Ms. Johnson called “a journey, but a labor of love.”

“When I started, not much had been written about the subject. There was this myth of pretty girls tracing color and that was kind of all that anybody knew about it.”

Ms. Johnson interviewed scores of women for the book, some surviving inkers or painters, as well as many of the offspring of the women whose story has been waiting to be told for decades.

“It was a very eye-opening experience,” Ms. Johnson said. “In terms of what existed on women’s roles in ink and paint, there was hardly anything at all. So we had to sort of think peripherally, and re-approach how we could use [the Disney Archives]. It took a different approach, a different way, a different thought process.

“We found some real gems during the research. Meeting members of family, retracing experiences, really opened things up quite a bit. We went through closets and under beds. We saw a lot of private collections.”

Ink & Paint measures a hefty 10″ x 13″ and is 384 pages in total. It is brimming with Ms. Johnson’s easy-to-read, yet thorough reporting, beautiful photos [many borrowed from willing interviewees] and wonderful archival illustrations. “As you can see by the out-of-control bibliography, I conducted an extensive amount of interviews and, quite frankly, with the number of ladies who were working at the Studio at the time, I just scratched the surface” on the women who were completely unsung and whose story was totally overdue.

I asked Ms. Johnson if there were any women still living who had worked on Disney’s earliest animated shorts and she was quick to respond. “Yes, we have one [although there may well be other ladies out there]: The amazing Ruthie Tompson.”

Ms. Tompson turned 107 back in July. As a young girl growing up in Los Angeles in the early 1930s, she’d often walk past the Disney Brothers Studios and peak through a window to watch the small team of artists at work. One day, Walt Disney himself invited her inside for a quick tour of the office. A few weeks later, Walt asked Ruthie and a few of her neighborhood pals to appear as extras in the latest Alice comedy they were working on.

“Going into the animation lab was a wonderful experience,” Ruthie told Ms. Johnson, “watching the drawings being made … What kid wouldn’t be fascinated? I’d sit there all day. Roy [Disney, Walt’s brother] would finally say, ‘Don’t you think it’s time for you to go home for dinner?'” Ruthie would go on to become one of the most respected members of the Ink and Paint Department.

Earlier this year, Ms. Johnson presented an event at the Motion Picture Academy, writing, creating and shaping it, which celebrated the trailblazing women of animation, both at Disney and at other animation studios. Ruthie Tompson was in attendance, as was Marge Champion [the fabled dancer who served as a model for the artists working on Snow White] and famed publicist Arlene Ludwig.

“With Ruthie in the room and with a handful of women in animation over the years up until today, we had at least one women who had worked on every Disney animated film ever created,” Ms. Johnson said. “A few weeks ago, it was my deep honor to present Ruthie with a copy of my book. We sat for a couple of hours and poured over it and talked about everything. It was sort of a yearbook to her.”

Ink & Paint is filled with many fascinating stories and a host of intricate details. For instance, everyone knows about Walt’s love of trains; but did you know that he had a soda fountain installed in his home so that his daughters, Sharon and Diane, could entertain their friends?

The book begins with an essay about women, titled “What I Know About Girls,” which was written by Walt himself. It appeared in Parents magazine in January of 1949. “That was something I came across quite a while ago and felt that if it wasn’t the introduction, at least it needed to be part of the book,” Ms. Johnson said.

There also are a number of sidebars sprinkled throughout the book, called Feminine First, which offer an in-depth look into some of the lesser-known figures in Disney animation and animation in general. “It became apparent that a number of women needed to be highlighted and featured,” Ms. Johnson said. “Women were really breaking ground in some pretty amazing areas. It was important to me that you heard as much of these ladies’ stories and their voices as possible.”

Ms. Johnson also delves into the working conditions the inkers and painters endured during those early days, even though “in the 1930s, the country was in the height of the Great Depression, so having a job at all, particularly at Disney, was like, as one of the ladies put it, ‘You won the lottery!’

“So there was a lot of enthusiasm, a lot of pure gusto and moxie going on among everyone.” Ms. Johnson also pointed out that at the time, members of the Ink & Paint Department made more money — 15 dollars a week — than a school teacher.

It also was a time when the concept of air-conditioning didn’t exist.

“In trying to keep things cool, they experimented with a few things,” Ms. Johnson said, “but always it was about retaining the clarity and pristine state of the cels. So dust and other things were an issue. when they had to institute smocks and hairnets and visors, it did get a little stuffy.” Heat and humidity not only made working conditions uncomfortable, they also played havoc with the integrity of the paint, often causing it to run or flake.

“If it was too hot, they would shut down and they’d come in during the evenings and early mornings. They [Disney] weren’t slave drivers in that regard, but they had to meet deadlines for the films. George The Ice Cream Man did a bang-up job during those hot summer months!”

Still, the hours were long and the work was tedious for the members of Ink & Paint.

It was the inkers’ job to trace over the artists’ sketches onto celluloid, using black ink. The desired qualities for an inker were accuracy to the pencil drawing; consistency of the pen line, and the ability to improve on the drawing. Inkers used pen points that ranged from fine to super heavy. According to Ms. Johnson, “Drawings were far more than ‘traced’ or ‘transferred;’ they were translated. Each pen stroke required interpreting the animator’s intent while keeping specific touches of individuality and style intact.” To achieve a sure line, Ms. Johnson added, “many inkers controlled their breathing between lines.” To maintain a steady hand, inkers would refrain from smoking or drinking coffee.

Once the cels dried, they were checked for uniformity and completion. If a cel didn’t measure up, it was sent back to be re-inked. Once each cel passed muster, it was sent to the painting department, where painters would begin the equally arduous task of adding color to the reverse side of the cel. A painter would use one color at a time on cel, put it aside to let the ink dry [about three hours] and then move on to another cel. Depending on the scene, a cel might require dozens of color applications.

“For the most part, they were young, they were excited and they loved what they were doing,” Ms. Johnson said. “There was a camaraderie, because they could see the end result. Their work ethic, too, was important. And their work was valued and appreciated.”

The inkers and painters were talented artists in their own right who were subjected to regular performance evaluations. Prospective new hires were given portfolio reviews every Tuesday. It was a grueling process. “Sometimes, even a woman’s signature or how they filled out their application forms” would be scrutinized. “Even though they came in with a high level of talent, they still had to go through an extensive training program.” If 40 women initially took part in a training session, perhaps three would make the cut and become either inkers or painters.

In reality, the level of talent and artistry in Ink & Paint was extraordinary. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Hazel Sewell, the older sister of Lillian Bounds, one of the company’s original inkers and painters who would go on the marry the boss, was in charge of the Ink & Paint Department and was the person who championed an escalation of caliber and talent within the ranks.

“Hazel was the first to institute an all-female department,” Ms. Johnson said. “She was the first to say that women were better … that they would get the work done faster and they’re harder workers.”

There was another woman, Mary Weiser, who single-handedly transformed inking and painting. In the 1930s, after Walt built a then-state-of-the-art facility designed specifically for the inkers and painters, Ms. Weiser developed the first and only paint lab for animation.

“At one point, when they began working on the color for Flowers and Trees in 1934, there were about 80 colors on the shelves,” Ms. Johnson said. “Transitioning from then to the early work on Snow White, they went from 80 shades of color to 1,500 shades, many of which were developed and cultivated … translucent solutions and adhesives and sprays and inks. They even found a formula for hand lotion. They needed something that wasn’t going to leave a greasy residue on the cels, and yet the hands of the artists needed to be supple.”

In her research, Ms. Johnson found a memo from the company’s production managers to the men in the in-between department [in-betweens are the drawings which create the illusion of motion]. “Walt was always mindful of the women’s working conditions,” Ms. Johnson said. “The memo to the in-betweeners said, ‘Watch your language. Walt wants this to be a comfortable place for the women to be working.'”

Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation is the story of the ladies who not only pioneered animation in the early days, it carries on to the women who helped develop the CAP computer-generated technology. “I felt like it was a more natural ending to bring you up to the CAP era. Who the women were and who was at the forefront of that technology, to sort of book-end it.”

Ms. Johnson, the author of Tinker Bell: An Evolution, is currently doing book signings and presentations at book stores and colleges in support of Ink & Paint. She’s hoping to turn her book into a college course. “It’s important not to let the title sway you,” she adds. “The book goes far beyond the women of Ink & Paint, but also tracks where women progressed and advanced into animation, editing, backgrounds, writing … virtually, every discipline of the animation process.”

“I’ve pitched this as a class,” she said, “and there are a couple of places already considering it.” She’s also in the early stages of developing a documentary.

Overall, “It’s been great fun. It was a real delight to meet some of these ladies and the children and the grandchildren. It was powerful. I can’t tell you how many came to me with boxes or portfolios or love letters. A whole bag of wonderful art and materials … often with tears in their eyes in jubilation.

“Many of their responses were: ‘Finally, they’re going to get their stories told.’”

Trending Now

There will soon be a NEW way to get to Disney World and Universal from...

Two rides have announced months-long closures at Universal Studios Orlando!

To get this NEW popcorn bucket, you'll have to grab some faith, trust, and pixie...

Don't miss out on these super low prices on Amazon for a bunch of cool...

Celebrating your birthday in Disney World soon? HOW FUN! Check out some of our favorite...

These are some of our favorite gift shops at Disney World and you might be...

A popular customizable Disney souvenir from Hong Kong Disneyland is about to make its stateside...

Rides in Disney World have a chance to temporarily shut down throughout the day. Some...

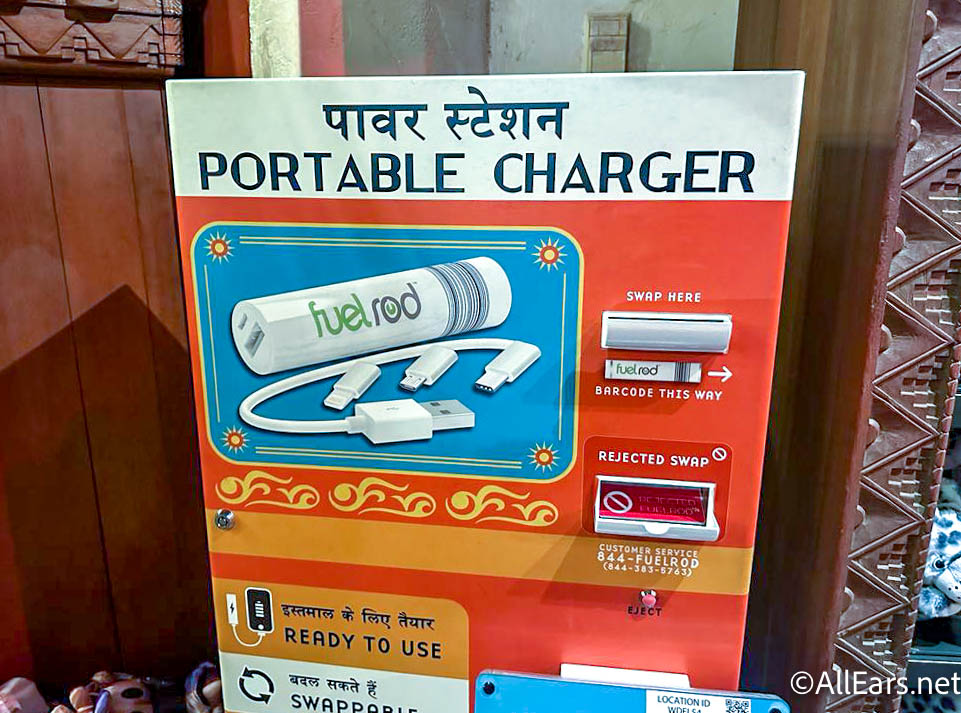

We took a trip to Adventureland and found some must-have souvenirs!

With the EPCOT International Food and Wine Festival right around the corner, make sure you...

A group of Disneyland employees have signed a petition to unionize. Here's what we know.

Here are the t-shirts that every Disney Dad will be wearing to Magic Kingdom from...

There are a lot of things that we get away with in Disney World that...

Let's talk about those souvenir photos that scream “This Is My First Trip to Disney...

Let's talk about some of the things Disney World hotel bathrooms urgently need!

The legendary music event, previously exclusive to IMAX, is having its global streaming premiere on...

We've become quite fond of these new (and very popular) bags, which is why we're...

A NEW Lug bag has been spotted at EPCOT!

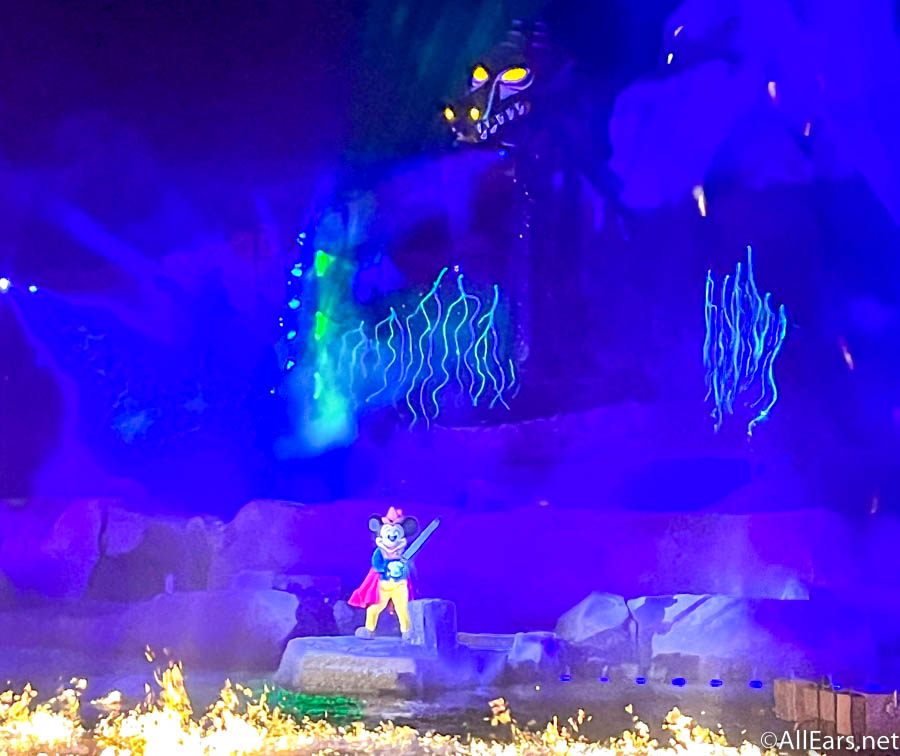

Checking out Fantasmic! next year? Make sure you know WHEN to catch it!

Is it possible to have the PERFECT morning in Magic Kingdom in only FOUR hours??...